This article is a collection of journal entries along my journey as a contributor in Google Summer of Code 2022. This doesn’t aim to be a detailed description of everything I did, but rather tries to give a general overview of how I got selected as a mentee, what I proposed to work on, and some of the golden nuggets of technical wisdom I managed to unearth while working on my project.

Que¿ What is this? Link to heading

To explain briefly, Google Summer of Code is an initiative by Google to bring new contributors into the world of open-source development. Interested developers (like me) can choose from one of the 200+ organisations that participate in the programme, pick a project idea (or suggest one of our own!) and write a technical proposal outlining how we intend to implement the solution. It is a great platform to network with a lot of amazing people from across the world, and work with some truly phenomenal programmers while getting to make contributions that are guaranteed to have real-world impact (not to mention that we’re paid a very generous stipend too).

How did I get selected? Link to heading

I began to look into the programme and what it entails in the beginning on 2022. Taking a look at the GSoC timeline, it became evident that I would get approximately a month to go through the list of accepted organisations, find a project I like, approach the mentors, discuss the idea, and make a few contributions before even thinking of writing a proposal. I never managed to make any serious progress until the last week of March, when I decided it’s high time I make some tangible headway. I decided on a very simple strategy to filter the orgs and projects - playing to my strengths. An org would be considered only if it had at least one project idea involving Go. After five hours of hard rock playlists and intensely reading a ton of project ideas, I had narrowed down my list to six orgs. Half an hour later, I was down to two. Five minutes later, I had picked the org I would be applying to.

CRIU is a Linux tool to checkpoint and restore processes. This org had listed a project that involved porting a binary image tool from Python to Go - right up my alley, and the perfect chance for me to get my hands dirty with systems programming. I emailed the mentor asking how to get started, and was provided with a great set of resources to learn about CRIU and CRIT (the Python tool). Two weeks later, I felt confident enough to attempt to write a blueprint of the solution I had come up with. Across the next two weeks, my mentor and I worked on converting my laughably tiny draft into a solid 11-page technical proposal. One month later, on my 20th birthday, fifteen minutes past midnight, I was informed that my project had been accepted.

Gimme dem details Link to heading

A detailed report of my work, along with the proposal, can be found here. I have also published the first draft of the proposal, just so you can see how it started and what it evolved into.

Tech tidbits from my work Link to heading

The implementation itself was very straightforward - figure out the Go equivalent of the existing Python code, and plonk it into a nice set of functions. The more interesting part was designing the library in a way that allowed it to be extensible and usable as both an importable package as well as a CLI application. The complete details can be found in my proposal, and I will not be elaborating on that again here. Instead, I would just like to share the weird gotchas I ran into and the esoteric hacks I used to fix them.

Make galore! Link to heading

The first speedbreaker was generating all the .pb.go files with the protobuf bindings for all the different image types. Doing this is relatively simple using protoc with protoc-gen-go, but the catch was that an option go_package = "the/pkg/path/" entry was required in every .proto file. Since adding this one line into all 73 files in the original criu repo would be madness, I had to come up with a workaround. protoc lets you define the package path as a flag while invoking the command, using --go_opt=Mpath/to/.proto=the/pkg/path. All I had to do was write this flag for every single .proto file. ded ×_×

By harnessing the power of GNU Make, I was able to achieve this with just two operations and a few variables :)

import_path := github.com/checkpoint-restore/go-criu/crit/images

proto_path := ./images

proto_files := $(sort $(subst $(proto_path)/,,$(wildcard $(proto_path)/*.proto)))

comma := ,

proto_opts := $(subst $() $(),$(comma),$(patsubst %,M%=$(import_path),$(proto_files)))

Let me explain what is going on here:

- First, create two variables to refer to the import path of the package, and the location of the

.protofiles. wildcardreturns a space-separated string of all files matching the given pattern. Take this andsubst(itute) the path prefix with the emptiness of the void, resulting in a space-separated string of just the names of all.protofiles.sortdoes exactly what it is supposed to, and additionally removes duplicates (if any).- Define a variable for the ‘,’ character, since it is used as a separator in the actual command.

- Now this last one is a little confusing, but bear with me.

patsubststands for pattern substitute. Withproto_filesas the input string, match any pattern (%) and replace it withM%=$(import_path), where the%refers to the matched pattern.substignores whitespaces, so$() $()is a nifty way to define a whitespace instantaneously. Simply take the output string of the previous command, and replace all spaces with commas.

Boom! I now have a comma-separated list of flags for every single .proto file that I can directly use as $(proto_opts) in my Make target.

Bless you, proto.Message Link to heading

The next hiccup was dealing with 73 different struct types offered by each of the .pb.go files. There were a few ways to deal with this:

- Declare the message struct as an

interface{}, and perform a type assertion depending on the type of image. Lots of conditional statements, a ton of checks for every function call, and a horribly inflexible approach. - Declare a separate function for each of the message types. While this is a more flexible and extensible option, it involves a humongous amount of repeated code to implement the processing for every single function. 73x copy-pasted code is definitely not a good example of 10x engineering.

A better solution was necessary. After a little bit of hunting in the protobuf docs, I discovered a life-saving abstraction - every single message struct implements a top-level proto.Message interface, that can be used to access the underlying methods. By using a variable of this interface type, a single switch statement is enough to assign the appropriate struct depending on the image type. Damn, that was some smart thinking by the protobuf devs!

Metaprogramming is love Link to heading

Great, we solved the issue regarding the different struct types. Now comes the problem of identifying which type to assign for which image. The hexadecimal value used by CRIU to identify the type of an image is called magic. criu provides a magic.h file with a set of definitions that look like #define MAGIC_NAME MAGIC_VALUE. The best way to do this in Go would be to use a map of strings to integers (octal, hex, decimal, they all eventually represent numbers). But how to populate this map? And how can we use it to assign the right struct type to a generic proto.Message variable? The answer to both questions is metaprogramming - code that generates more code. Noice!

To solve the first issue, we can write a Go script to parse magic.h, identify lines in the required format, and generate a magic.go file that creates and populates a map[string]uint64 with all the parsed values. Go provides fmt.Fprintf, which conveniently lets us generate formatted strings and write them to a file. You can find my script here.

The solution to the second issue is just an extension of the first. Iterate over the map of magic values and generate a switch case for each magic, resulting in something like this:

func ProtoHandler(magic string) (proto.Message, error) {

switch magic {

case "MAGIC_ONE":

handler = &MagicOne{}

case "MAGIC_TWO":

handler = &MagicTwo{}

// ...

// Similar cases for all other magics

}

}

This works for 99% of the magics and their respective proto handlers. For the odd 1%, we can just add in the case manually.

Object-oriented nightmares Link to heading

Go doesn’t have classes. Instead, it has structs with receiver functions that act like class methods. What about inheritance? Go tries to answer this with a concept called struct embedding, and creates a chaotic mess with bizzarely unintuitive behaviour that takes forever to debug. In fact, this topic is bad enough to deserve its own post. You can read about it in detail here.

:s/.*[Rr]eg(ular)?\s?([Ee]x)((press)ions)?.*/\2\4way to hell Link to heading

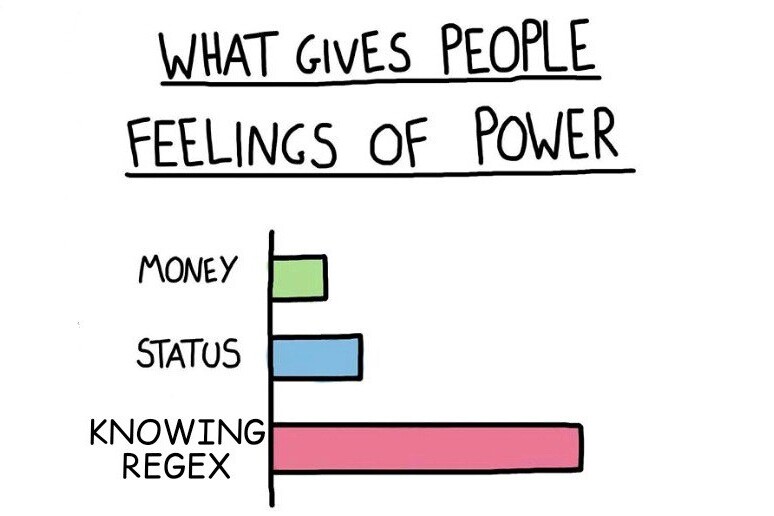

If you figured that out, congratulations! You now know what most people think of regex!

But no. If you know enough to decipher that phrase, you most likely don’t share that opinion, and I’m with you.

Regex has got to be one of the coolest innovations on this planet. For most people, writing regex is a real-life horror story - you just can’t seem to get it right, and when you finally think you’ve nailed it, you break production :/ But if you learn it correctly, you join the pantheon of programming gods as a minor diety of pattern matching :)

The E2E(end-to-end) and integration test for library use the image files from a dumped process to test if everything is working fine. In the process of doing this, they generate certain temporary files with the same extension.

What we have: A

test-imgsdirectory with:.imgfiles generated by CRIU.test.imgfiles generated by the integration test.json,.json.img,tmp.XXXXXXXXXX.json, andtmp.XXXXXXXXXX.imgfiles generated by the E2E test

What we want: A list of

.imgCRIU files, without the other.imgfiles

Clearly, we cannot use ls test-imgs/*.img as we will end up listing the files generated by the tests with the original ones. So how do we retrieve only the original image files to use for testing? Simple - just write a regular expression to match the files having a single period(.) in the name!

insert drumroll

^[^\.]*\.img$

Amused? Confused? Feeling like you got trolled? Let’s break this down:

^: The starting of the word[^\.]*: Any number of characters that are not(^inside brackets denotes negation) a period(.). The period itself needs to be escaped as it is also the regex symbol for a wildcard.\.img: The.imgextension$: The end of the word

There you go! If the file name contains more than one period or doesn’t end with .img, it is not matched.

A New Hope Link to heading

GSoC was my portal to explore systems programming. I think most people are unaware of what exactly goes on behind the scenes when they switch on their computers, even if they’re doing nothing. A tiny glimpse of how a kernel operates is enough to leave you astounded at the stupendous amount of processing that occurs with every single operation, and really opens your eyes to how complex modern computers are. The nature of my project let me dive deep into the inner workings of Linux and the marvels of memory management, inter-process communication, file I/O, and a ton of other topics. It also induced a strange affection for C/C++, which in turn led to me exploring compiler design and LLVM (which is another milestone of technological evolution).

And thus, as one journey ends, it brings with it a new hope to venture into the unknown, and unearth the hidden treasures of modern computing.

We know very little, and yet it is astonishing that we know so much,

and still more astonishing that so little knowledge can give us so much power.

– Bertrand Russell